By John McMahon

For decades now something tragic has been happening after sunset: the solemn majesty of the starry sky is disappearing before our very eyes as excessive and misdirected lighting, known by the popular term light pollution, spreads year by year. In short, the natural darkness of night has succumbed to urban and suburban outdoor lighting. Truly dark skies have retreated; and as a result, many rural communities far from light sources have now lost their “country skies,” once a defining feature of life away from cities.

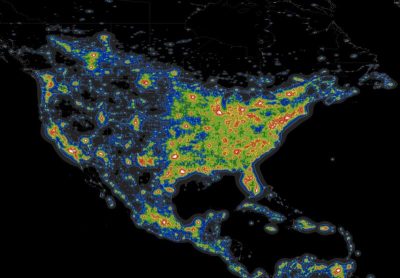

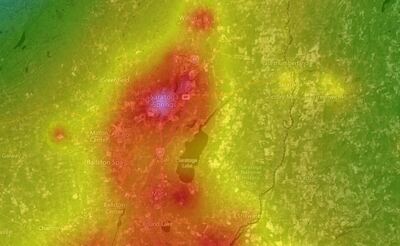

While astronomers have noted and decried the problem of light pollution for well over a century, it is now estimated that more than three quarters of ordinary North Americans can no longer see the Milky Way because of sky glow from artificial outdoor lighting. What is more, a recent study has shown that since 2011 sky brightness has increased worldwide by 10% annually. That means that even to the casual observer the loss of darkness after sunset, both in the starry expanse above our heads and across the terrestrial nocturnal landscape, is becoming an unavoidable reality. Indeed, across much of the globe naturally occurring darkness has now been relegated to specially designated dark-sky preserves in regions far away from where ordinary people and their families live.

Light pollution affects the natural world

The loss of the sky’s inspirational beauty is not just a problem of astronomy and aesthetics, however; we are only now beginning to discover how light pollution is devastating the natural world at night all around us. Darkness, as part of the Earth’s regular pattern of day and night, is the condition under which virtually all plants and animals, including humans, have evolved over millions of years. All terrestrial and aquatic life has functioned for eons within this daily cycle. Recent studies have shown, though, that the intrusion of continuous artificial lighting into the formerly dark natural habitats of nocturnal animals effectively fragments them. It can also disrupt behaviors crucial for animals’ survival, including mating and reproduction, communication, hunting and foraging as well as migration.

The adverse impacts of light pollution on specific animals are stark reminders of the seriousness of the situation. Among vertebrates, for example, bird predators like owls use faint moonlight and starlight in an otherwise dark environment to find prey, and artificial illumination may interfere with their success. Particularly in rural settings, outdoor lighting and general sky glow have been shown to alter avian behavior such as mating songs and choice of nesting sites. In addition, artificial lighting and bright skies can disorient migrating birds or other animals that move seasonally.

Bright lights directly change animal behavior. Some bat species will crowd rural streetlights to feast on the number of insects drawn to the illumination while other bat species avoid lights. This can upset the natural ratio of species in any given ecological niche and cause an imbalance in bat populations. Fear of predators in lighted spaces may cause some animal species to forage less. Some aquatic fauna react to light in ways that expose them more readily to nocturnal predators. Frogs active after sunset have shown altered mating and calling behaviors when exposed to light levels different from the norm that they’ve been used to. Salamanders may more easily detect breeding rivals, meaning that they would spend more time challenging other suitors and less time seeking food thus potentially weakening them.

Invertebrates, especially nocturnal insects are at serious risk. As concern rises worldwide about the loss of pollinators (from pesticides, habitat loss and invasive species) the threat from light pollution to nocturnal insects in general and pollinators in particular is of special concern since it is so widespread. Research on moths, which pollinate many plants crucial to both wildlife and human well-being, has shown that they were instinctively and helplessly drawn to street lights. This distracted them from the night-blooming flowers that they had evolved to visit. On the other hand, the study also demonstrated that by turning off lights for half of the night and restoring several hours of true dark-sky conditions, their normal pollination patterns were not affected. Another recent study has demonstrated that the rhythmic flickering light of fireflies used to attract their mates is rendered less effective by the presence of bright lights, and this results in delays in egg-laying or the reduction of the number of eggs.

You can make a difference

While research into such ecological implications of artificial light is still a young field, more scientific evidence of its harmful effects on the natural world at night is being regularly documented. Until the weight of that data is sufficient to change lighting practices on a large scale, however, everyone can help make a difference in an individual way by following dark-sky appropriate lighting practices where they live and work. The most effective of these are very simple and can be implemented with little or no special effort.

- Use only the amount of light necessary for a specific purpose since brighter is not necessarily better.

- Make sure that any light being used is directed properly so it does not splash everywhere for no good reason.

- Ensure by proper shielding that no illumination is allowed to spill upwards above the horizontal plane of the fixture.

- Mount all lighting fixtures at the proper height to do their job most efficiently and to reduce vision-impairing glare.

- If light is absolutely necessary after dark, refrain from lighting the entire night long by using motion sensors or timers to limit light to only those periods when it’s actually needed.

Finally, remember that outdoor lighting is like salt: just the right amount enhances things; but too much ruins everything.

Part one of a series. Stay tuned for future posts on Dark Skies.

For more information on how you can help to save the night, see the International Dark-Sky Association’s website on sound residential lighting practices: https://www.darksky.org/our-work/lighting/lighting-for-citizens/residentialbusiness-lighting/

More Sustainable Saratoga resources for encouraging and protecting our local wildlife