Why turn your lawn into a meadow?

Lawns are ecological dead zones that use huge amounts of resources like pesticides, fertilizers, fossil fuel and water. They do not support, and in many cases actively kill, pollinators, birds and other wildlife, and they require continual care. While some lawns are useful, in that they provide spaces for play, pets, and socializing, most lawns are simply vacant expanses of green that people maintain for socially-constructed aesthetic purposes. Lawns are associated with wealth and tidiness and are serviced by an expansive industry that promotes their continuation for its own profit.

A growing number of people are concerned about the ecological impact of lawns and the missing habitat that lawns have displaced. The Homegrown National Park movement, the Xerces Society and other groups encourage people to replace their lawns with native plants that can support native animal species, like insects and birds. Many people are incorporating native plants into their garden beds but if you want to take it up a notch, consider replacing all or part of your lawn with a meadow.

Before planning a meadow, it is important to identify your soil type and planting hardiness zone. In Saratoga Springs, NY, we are in USDA Hardiness Zone 5a, have around 45 inches of precipitation a year, and most often have sandy or clay soils. In order to plan a meadow that will thrive in your location, you should try to identify your soil type. Cornell Cooperative Extension can help you with soil identification and pH testing if you don’t know.

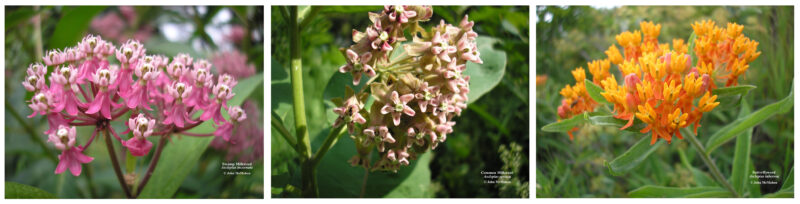

Milkweeds

What is a Meadow?

A meadow is a tall grassland mixed with perennial flowering plants that are not woody. Meadows can be maintained by fire, grazing, dry conditions or, in the case of yards, annual mowing early in the spring or late in the fall when the mowing will not interfere with the life cycles of the insects overwintering in the soil. Although excessive mowing is neither necessary nor desirable to maintain a meadow, without annual mowing trees will move in and shade out the meadow plants. Meadows do not need chemical inputs, do well in poor soils, and require sun at least half of the day.

Preparation: Kill Your Lawn

To establish a meadow, you first need to get rid of the plants, presumably turf grasses, that are growing where you want the meadow to be located. There are a couple of ways to do this that do not use herbicides like Roundup which are known to have disastrous effects on the eco-system as well as probable human health risks. One way to kill your lawn is to till the area of the grass you wish to convert to meadow, let it lay fallow until grass and weeds start to poke up, then till it again before planting. Rent or borrow a heavy-duty tiller for this job, turf is tough. Alternatively, you can use the lasagna method of soil preparation by placing a layer of cardboard over the lawn area in the late autumn or early spring, covering it with compost, letting it rot for at least six weeks, then planting into it directly. The lasagna method is an improvement on black plastic in that you are not left with plastic waste that cannot be reused or recycled.

Plugs or Seeds?

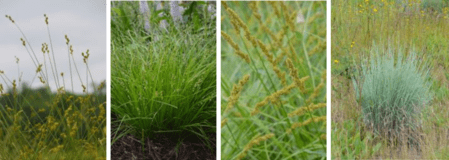

Sedges and Grasses

You can use either landscape plugs or seeds to start your native plant meadow. Plugs survive better because they have already germinated and started to grow, but seeds are cheaper and less labor intensive. In order to have a natural looking meadow, if you are using plugs you should develop a random planting map showing you where to place your plugs throughout the area you so that no pattern is discernible. If you are using seeds you should buy a native-plant meadow seed mix adapted to your climate zone and region, or buy a number of packets of seeds that you want to use and combine them in a large bowl. Mix the seeds well into a bucket or other container of damp sawdust or kitty litter. Sprinkle the seed-laden sawdust evenly over the ground you have prepared for your meadow. If it is a large area, divide the field into sections, then divide the seed/sawdust mix into an equal number of parts and apply one part of seed/sawdust mix to each section of field to get a uniform distribution. Seeds do not need to be buried if they are in contact with tilled earth or compost. You can do a mixture of plugs and seeds if you want. And, of course, plugs and seeds should not be treated with pesticides since part of the purpose of your meadow is to feed wildlife.

Choose Your Native Plant Species

Fall blooming Asters

The most important part of this is to pick plant species that do well in your region and soil type and that are all about the same height. If you have a mix of tall and short plants, the short plants will be shaded out and will not establish. The best height for meadow plants tends to be about two-and-a-half to three feet since taller plants often fall over in wind and rain. A mixture of blooms times is optimal, as is having a mix of native grasses and native flowering perennials. The Prairie Moon Nursery website has an excellent sidebar function that allows you to apply filters to the selection of seeds and plugs it sells so you can identify species of plants that are the height you want, that grow in your soil type, that are adapted to your part of the country and that will grow in your USDA Hardiness Zone. It is preferable to have a mix of colors and bloom times to optimize the value of the meadow as a food source for wildlife. In general, if you are planting both grasses and perennials, you should plant the grasses first, then the perennials a few weeks later. You should have a mixture or around 15 to 25 plant species, roughly half of which should be grasses.

Nurse Crops

Consider using a nurse crop for the first couple of years. A nurse crop is an annual crop that will help protect your young plants from excessive sun, help hold the soil in place while the roots of your meadow plants develop, and provide some color while your meadow is getting established. You can use almost any winter-killed cover crop like annual rye or buckwheat but be careful not to sow it too thickly since you don’t want the nurse crop to shade out and kill your meadow plants. Plant nurse crops in the spring.

Spot Weeding

You may need to weed out undesirable invasive species from your meadow while it is being established. You can do this with a stirrup hoe or dibble stick. After a few years, your meadow can take care of itself and will no longer need weeding.

Watering

If it rains weekly, don’t water. In a droughty year, keep your eye on soil moisture, test it with your finger, and only water if the soil is completely dried out. If you overwater, your plants will not develop the healthy roots systems they need to thrive without care. You want an independent meadow, not a coddled lawn!

Remember that gardening is all about trial and error. Some things will work, some things will not, but there is always next year!

Resources

Adapted from a webinar by Penn State Extension, available at https://psu.mediaspace.kaltura.com/media/Turning+Lawns+into+Meadows/1_pr3dxac5

Owen Wormser’s book, Lawns Into Meadows: Growing a Regenerative Landscape (Stone Pier Press, 2022) is a great reference

How to Kill Grass Naturally, Using Newspapers, David Beaulieu, The Spruce, May 2019

Sustainable Landscaping, New York Department of Environmental Conservation

Sources of native seeds and plants

Sustainable Saratoga’s Pollinator Palooza Native Plant Sale

For more information about native plants and their benefits to Pollinators, see our Pollinator Pages