Many native plant species provide important support for insect pollinators such as flies, bees, ants, wasps and hornets as well as butterflies and moths. In return these pollinators facilitate the fertilization of the plants and ultimately their reproduction and seed dispersal. While some insect pollinators engage with only a limited number of plants during their particular blooming period, many others are less discriminating. These latter may visit a wide range of plants in flower over a longer period of time, and a large number of such plants can be easily grown under ordinary garden conditions.

Garden design for native plants stands in sharp contrast to the managed and lockstep plantings of the commercially produced non-native plants that are regularly encountered in lawn-dominant residential developments, on sprawling corporate campuses and in manicured public parks. Natural gardens require a more subtle approach for the proper interaction of pollinators and native plant species to succeed. Above all, the underlying premise should be that whatever its location or size, a garden of native species avoids rigid monotony. In fact, to serve the entire community of pollinators well, profusion is far better than precision. The cultivation of specific native plants will not only provide needed support for pollinators in general but will also provide an unbroken succession of ever-changing floral color and foliar texture from early Spring until late Fall.

The gardener who wishes to grow native plant species in the natural garden would do well to consider rescuing plants doomed to destruction by impending development, by landscaping practices on private property or by roadside mowing and spraying, always getting permission from the landowner first, of course. Likewise, common pollinator plants such as goldenrod and asters that have been uprooted from residential properties may be found piled at the curbside awaiting removal by municipal highway departments. If secured before they dry out, they can be saved by trimming back their foliage and planting them in cool and shaded locations until they can recover. Many of these same plants can also be grown from seeds or cuttings taken at appropriate times of the year.

What follows is a brief overview of easily grown and common flowering plants proven to be particularly useful in the pollinator-friendly natural garden. It is not comprehensive but rather provides a simple guide for the native plant gardener who wants a succession of bloom over the growing year. The plants appearing below are the most commonly encountered and are listed in a very rough order of their blooming period.

Spring (March, April and May)

Most of the early-blooming wild plants below are suitable for partially shaded and/or wooded locations.

Skunk Cabbage

Skunk Cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) is the earliest pollinator-friendly native species, emerging in wetland margins and wet woods in late winter, in some cases even protruding through the last vestiges of snow cover. Under its curious protective floral hood is a knob of tiny yellow flowers that attract flies with an odor that resembles rotting flesh. The Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) is a familiar woodland species that also attracts insects with its aroma. It flowers in mid-Spring.

Violets

Violets (Viola spp.) of many different kinds appear in the very early spring (Sweet White Violet, V. blanda, e.g.) and continue in bloom into late May. Many of them can be grown from collected seed, and some will eventually appear on their own if an area is left alone. Although they may self-pollinate, they do attract a variety of bees as well as some smaller insects and butterflies.

Wild Ginger

Wild Ginger (Asarum canadense) is small plant of the woodland floor whose curious purplish flowers are important to early pollinators such as flies. If introduced to the wild garden, it can serve as a satisfactory groundcover.

Trillium

Wakerobin (Trillium erectum) is a low-growing woodland plant that emerges from a rhizome under dappled shade. Its dark purple flower has a disagreeable odor that attracts flies to pollinate the smelly flowers. There are several other species of Trillium. The largest is the White Trillium (T. grandiflorum) and the showiest is the Painted Trillium (T. undulatum) with a splash of red at its flower’s center. Given the proper conditions in semi-shaded woods, all are relatively easy to grow.

Trout Lily

Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum) sends up a single six-parted yellow blossom held less than a foot above a pair of green and brown-speckled leaves that lie close to the ground. It grows from a bulb and forms large colonies but is difficult to cultivate. Bees and flies are frequent visitors to these spring flowers.

Solomon’s Seal

Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum biflorum) can be found in woodlands as tree leaves begin to unfold. It has an arching stem that emerges from a creeping rootstock. Underneath its wide and pointed leaves pairs of delicate bell-like flowers hang suspended. Bees and a variety of smaller insects pollinate these flowers, and the blue berries that follow in the summer may be collected and planted in the Fall.

False Spikenard

False Spikenard (Maianthemum racemosum) is a common woodland plant that superficially resembles the Solomon’s Seal, but its prominent mass of tiny, feathery white flowers appear at the summit of it stem. Its red berries may be collected and sown in the Fall.

Anemones

Anemones (Anemone spp.) make up a group of attractive plants with showy white blooms that attract bumblebees and other winged insects. With the exception of the low and delicate woodland Windflower (A. quinquefolia) that appears in very early Spring, they grow a foot or more tall and bloom from mid-Spring into very early Summer. Noticeable along partly sunny wood edges, open fields and forest openings, they can be grown from collected seeds.

Spotted Geranium

Spotted Geranium (Geranium maculatum) appears along sunny wood edges and in thickets in mid-Spring. Its purple flowers with five petals host honeybees along with smaller native bees and flies. It can be grown from seeds collected after flowering. Several other species in the genus provide similar benefits to pollinators.

Summer (June, July and August)

With some exceptions (marked with *), the native plants below are suitable for sunny and open locations. Many are strong growers that can survive a variety of adverse growing conditions.

Wild Leek*

Wild Leek (Allium tricoccum) is a woodland species whose leaves appear in Spring but wither away in early Summer before its flowers emerge from an underground bulb. The flowers are favored by bees because they can produce a good deal of honey. Wild Leek can be used in connection with some of the Spring-flowering plants already mentioned. Both the leaves and bulbs are edible, but care should be taken not to overharvest any one stand.

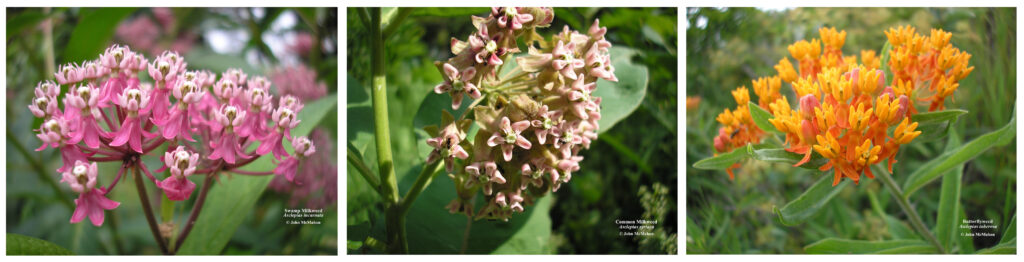

Milkweed

Milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) are some of the most valuable plants for supporting pollinators as well as for being the sole food source for Monarch Butterfly larvae. All feature colorful flower clusters. Common Milkweed (A. syriaca) is ubiquitous and blooms the earliest, but it should be intentionally planted on private properties because it is regularly eradicated from developed and agricultural land. The orange-flowered Butterflyweed (A. tuberosa) favors dry terrain, and Swamp Milkweed (A. incarnata) prefers wet locations. All can be grown from seed.

Blue Vervain

Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata) produces tall spikes of nectar-rich blue flowers favored by many insects, especially bumblebees. In addition, it serves as a host plant for caterpillars of the Common Buckeye, Junonia coenia. Blue Vervain prefers sunny moist locations and can grow to four feet or more. Once established, it self-sows freely.

Bergamot

Bergamots or Bee-balms (Monarda spp.) are tall mints, whose tubular flowers are favorites of pollinators like moths, bees and hummingbirds. They also serve as hosts for the larvae of several native moths. The colors of the flowers vary according to species. Monarda didyma, also known as Oswego Tea, features brilliant red blooms; those of the Wild Bergamot (M. fistulosa) are light purple. They do best in moist locations and are easy to grow. Cultivated varieties of the genus show up frequently in gardens as well.

Lobelia*

Lobelias (Lobelia spp.) produce both red (L. cardinalis) and blue (L. siphilitica) lipped, tubular flowers arranged on a tall spike. They attract bees and butterflies as well as hummingbirds. Both are easily grown from their dust-like seeds and will self-sow in moist or wet locations. They should have some shade during hot afternoons.

Coneflower

Coneflowers (Rudbeckia spp.) are easily-grown pollinator plants. The familiar Black-eyed Susan (R. hirta) and the much taller Green-headed Coneflower (R. laciniata) are examples of species suitable for the natural garden. The latter has a long blooming period. A related plant, the Eastern Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), is a favorite of pollinators as well.

Touch-Me-Nots

Touch-Me-Nots (Impatiens spp.) have delicate, hanging tubular flowers that are bee favorites. The Spotted Touch-Me-Not (I. capensis) offers its pollinators a multitude of mottled orange blossoms, while the blooms of the Pale Touch-Me-Not (I. pallida) are light yellow. These leafy, bushy annuals, also known as Jewelweeds, prefer wet or moist locations and are easily grown from collected seeds. They will also self-sow readily.

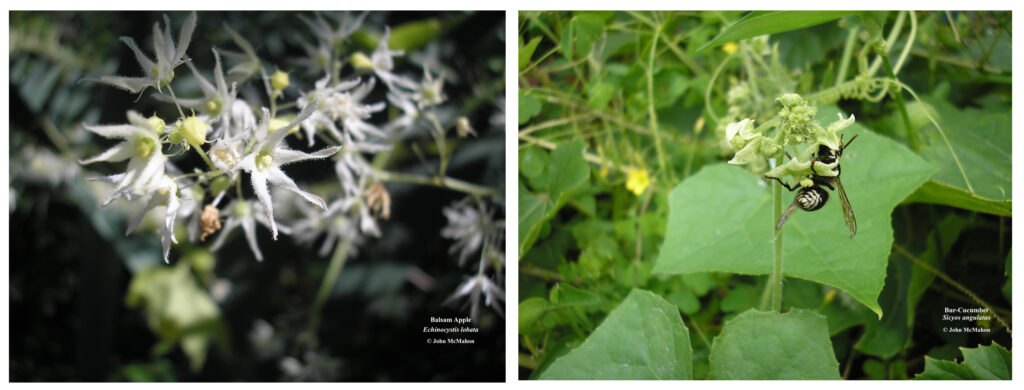

Wild Cucumbers

Wild Cucumbers are fast-growing annual vines that are pollinator-friendly and easily grown from seeds collected in the Fall. The Balsam Apple (Echinocystis lobata) sends up fragrant feathery spikes of white male flowers. The flowers of Bur-Cucumber (Sicyos angulatus) are less showy but are favorites of wasps and hornets. Both vines favor sunny, damp locations and can be grown on fences and hedges or cultivated as leafy screens on porches and decks.

Late Summer into Fall (August, September, October and November)

Members of the Aster (or Composite) Family make up the bulk of the late-season pollinator plants. While some species may begin to bloom as early as July, most of the plants below should also be considered as the primary source of food for pollinators during the Fall months. In fact, some asters and goldenrods easily survive early frosts and will continue to flower until a hard freeze.

Wingstem

Wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia) is a tall, yellow-flowered native that has long been a favorite of beekeepers for the large amount of honey that it can provide for bees.

Sunflower

Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) are major benefactors of insect pollinators. Some are familiar both in their wild and cultivated forms (H. annus, e.g.) while others grow in a variety of environments, including damp woods and thickets (like H. decapetalus). All are readily grown from the seeds that are produced in the typical floral head known to all. One species, the so-called Jerusalem Artichoke (H. tuberosus), can be propagated simply by digging its profusion of (edible) underground roots, but care should be taken to contain the plant as it spreads aggressively and is very persistent.

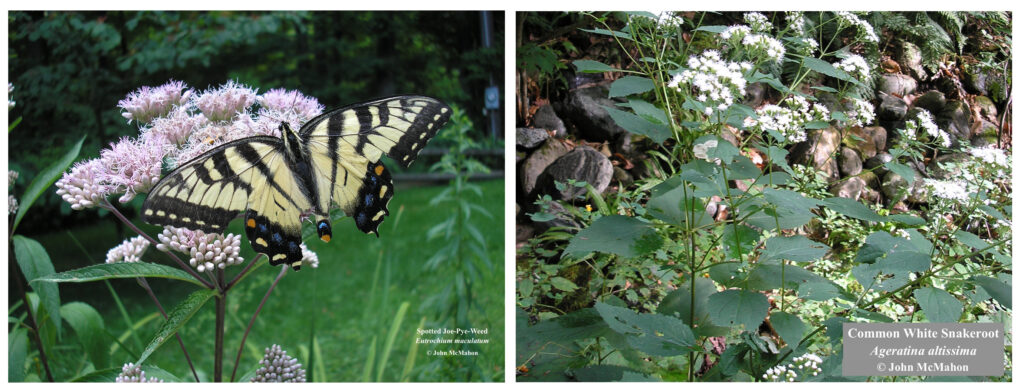

Thoroughworts

Thoroughworts and their kin (Eutrochium spp., Eupatorium spp., Ageratina spp.) are familiar late-summer wild plants with fuzzy, flat-topped flower clusters that appeal to many kinds of pollinators. Most prefer damp locations with a good deal of sun. Several species of the rosy reddish Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium purpureum, e.g.) can commonly be found along roadside ditches and stream sides. Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) is a bit more tolerant of drier locations. White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) and some of its relatives may bloom well into October. All can be grown from the many seeds collected from the dry flower clusters that persist into winter.

Goldenrod

Goldenrods (Solidago spp., Euthamia spp.) bloom from mid-July (S. juncea) until well into Fall (S. caesia). As the flowering year wanes, they are very important as pollinator plants for many insects. Easy to grow, they can provide for several months of successive bloom in both sunny and semi-shaded locations. Ranging from low-growing species that prefer dry fields (like S. nemoralis) to the taller and strong-growing S. rugosa and to those that thrive along damp, shaded wood edges (like S. flexicaulis), there is a goldenrod for every natural garden environment. A September field aglow with goldenrod and alive with pollinators like bees, wasps, butterflies and beetles is an unforgettable visual and auditory experience.

Aster

Asters (Symphyotrichum spp., Eurybia spp.) are our premier late-season pollinator plants, blooming in a wide variety of situations. Tall, bold species like New England Aster (S. novae-angliae) fill the fields and roadsides with purple and yellow flowering heads while the delicate blooms of the White Wood Aster (E. divaricata) brighten semi-shaded woods. The Heart-Leaved Aster (S. cordifolium) and the Calico Aster (S. lateriflorum) are particularly desirable because of their compact bushiness, the sheer profusion of their flowers and their lengthy period of bloom All the asters, however, are essential sources of nourishment for insect pollinators, and there is an aster species that will fit into any natural garden, however small or large. Asters can be grown from collected seed.